Anti-aging and anti-carcinogenic effects of 1α, 25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 on skin

Abstract

Photoaging and carcinogenesis are facilitated by oxidative stress, inflammation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. Oxidative effects include DNA damage, membrane oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and alterations in the expression of p53 and antioxidant enzymes. The inflammatory and angiogenesis mediators include interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-8, transforming growth factor-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor. ECM remodeling includes alterations in the expression and organization of collagen, elastin, matrix metalloproteinases, and elastase. 1α, 25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and ECM regulatory properties, and can counteract the processes that facilitate photoaging and carcinogenesis. This review provides an overview of the beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation at a molecular level, followed by a brief discussion regarding its use as a supplement.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

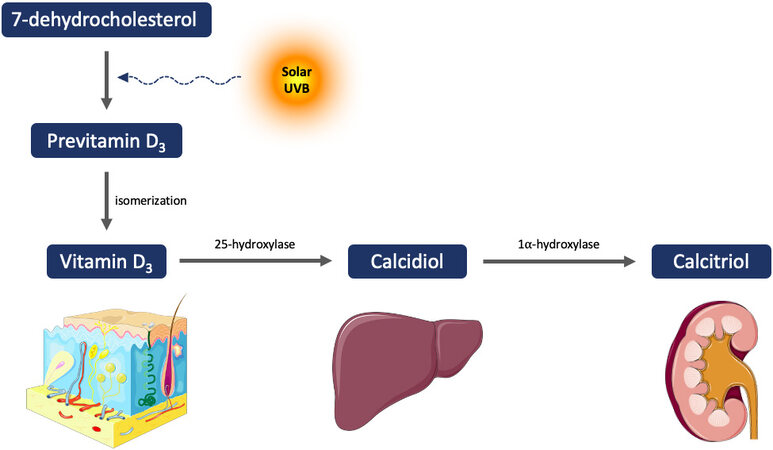

Vitamin D (VD) is a prohormone involved in a broad range of functions in the organism that has been shown to exert protective effects against several types of cancer[1] and skin aging[2], among others. In the human epidermis, exposure to sunlight - ultraviolet B radiation (UVB, 280-315 nm) - promotes the transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol to previtamin D3, which undergoes thermal isomerization into cholecalciferol, also known as vitamin D3 [Figure 1]. Cholecalciferol is then hydroxylated in the liver to 25-hydroxycholecalciferol or calcidiol, and further hydroxylated in the kidney into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 or calcitriol, which is the biologically active form of VD[3]. Calcitriol, therefore, acts through an intracellular receptor, vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is ubiquitously expressed in most nucleated cells[4]. Calcitriol exerts antiproliferative, antiangiogenic, pro-differentiating, and antiapoptotic effects[5].

Recent research has identified an alternative vitamin D activation pathway through CYP11A1[6-8]. CYP11A1-mediated metabolism of vitamin D results in the production of 20-hydroxyvitamin D and its hydroxymetabolites. These byproducts have antiproliferative, differentiative, and anti-inflammatory effects in skin cells, comparable or greater than those of calcitriol[9]. Additionally, these metabolites improve different defense mechanisms against UVB-induced DNA damage and oxidative stress[9,10]. Alternative nuclear receptors for vitamin D hydroxyderivaties have also been identified, such as retinoid-related orphan receptor (ROR) alpha and ROR gamma[11-13].

Both skin aging and cancer have been associated with increased cellular oxidative stress, the release of inflammatory and angiogenic mediators, and abnormal extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, among others[14-17]. Other non-classic effects of VD include cell growth suppression, apoptosis regulation, modulation of immune responses, control of differentiation, or antioxidant effect, among others[18], suggesting that VD might be of potential relevance in skin aging and cancer.

OXIDATIVE DAMAGE

Cellular oxidative stress arises when the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals, superoxide, or hydrogen peroxide, exceed the ability of endogenous antioxidants or antioxidant enzymes to quench them[19]. These antioxidant systems include glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase[20,21]. Oxidative damage occurs during the intrinsic cutaneous aging phenomenon, and it is exacerbated by exposure of the skin to damaging physical or environmental pollutants such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation, heavy metals, or benzene derivatives[22-26]. UVA radiation (315-400 nm) reaches the dermis, causing DNA damage mainly through oxidative stress, whereas UVB (280-15 nm) reaches the epidermis and causes direct DNA damage as well as oxidative stress-related DNA damage[20,21,23,24,27]. In addition, exposure to pollutants also results in detrimental alterations through direct oxidative stress[25,26]. Intrinsic skin aging is also associated with diminished levels of steroidal hormones, among others, thus, resulting in the thinning and fine wrinkling of the skin[22]. Additionally, ROS produced by extrinsic damaging factors correlates with coarse wrinkling.

In relation to carcinogenesis, numerous studies have demonstrated that ROS are able to induce mutagenesis through diverse mechanisms. In fact, nucleotides are highly susceptible to free radical damage, and their oxidation promotes base mispairing, leading to mutagenesis[28]. One of the best-characterized mutations caused by ROS is the conversion of guanine into thymine, as a result of guanine oxidation at the eighth position, resulting in 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanine (8-OHdG) production[29]. This last nucleotide base tends to pair with adenine instead of cytosine, leading to mispairing and mutagenesis. These mutations have been extensively found in different types of skin tumors[30]. Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation has mutagenic effects beyond the time of exposure due to ROS production, leading to the so-called dark-cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD)[31]. ROS generated through UV radiation, superoxide and nitric oxide, undergo a series of reactions involving melanin fragments resulting from its photochemical degradation. Excited-state triplet carbonyls are formed, which transfer their energy to DNA bases leading to the formation of CPDs[32]. Additionally, oxidative DNA damage has been seen to be accentuated by the depletion of glutathione in fibroblasts and melanoma cells[33]. Moreover, oxidative stress can also induce lipid peroxidation and cell membrane damage that leads to the leakage of intracellular proteins to the exterior[34,35]. Active substances with antioxidant properties such as VD, lutein, P. leucotomos extract and

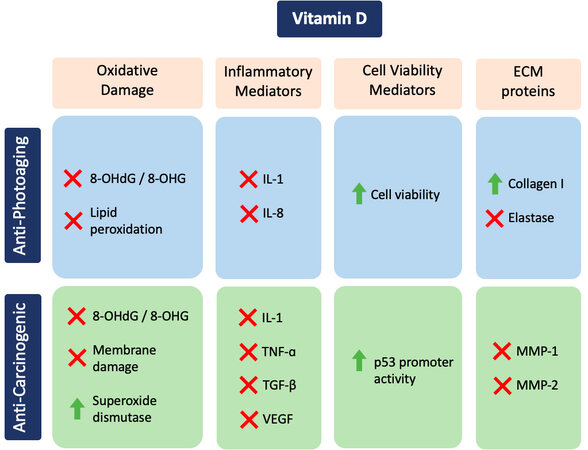

VD is photoprotective as it inhibits UV radiation-mediated oxidative DNA damage[34,35], and induction of cellular skin defenses[40,41]. VD inhibits oxidative stress and tissue damage induced by exhaustive exercise and 2,2’-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonate) oxidation in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and met-myoglobin[34,42]. It also inhibits oxidative DNA damage in non-irradiated or UV-radiated fibroblasts and melanoma cells; prevents membrane damage in UV-radiated fibroblasts and melanoma cells; decreases lipid peroxidation in non-irradiated and UVA-radiated fibroblasts; stimulates expression of superoxide dismutase in melanoma cells[34,35] [Figure 2]. These data emerged from in vitro experiments in which different treatment conditions were evaluated: non-irradiated, UVA-irradiated, or UVB-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts, and melanoma cells (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC) were incubated for 24 h in the presence of different doses of VD (0, 0.02, 0.2, or 2 μM). Cells were analyzed for products of oxidative damage and for membrane damage and lipid peroxidation. A competitive DNA/RNA oxidative damage ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical) revealed lower levels of 8-OHdG and 8-hydroxy-2’-guanine in VD-treated cells. The supernatants of VD-treated cells also displayed lower levels of lactate dehydrogenase, which is an indicator of membrane damage. Finally, a kit that enables hydroperoxide to oxidize ferrous to ferric ion, forming a colored adduct with xylenol orange {“3,3’-bis[N,N-bis(carboxymethyl)aminomethyl]o-cresolsulfonephthalein, sodium salt”} revealed that VD decreased cellular lipid peroxidation. In summary, these results showed that VD reduced the formation of 8-OHdG and CPDs caused by oxidative stress through the reduction of ROS in UV-irradiated skin explants, as well as other mutagenic alterations such as thymine dimers or 8-nitroguanosine[43].

Figure 2. Table summarizing the anti-photoaging and anti-photocarcinogenic effects of vitamin D. Green plus sign means upregulation; Red X denotes inhibition. IL-1: Interleukin-1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-8: interleukin-8; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; MMP: matrix metalloproteinases; 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanine; ECM: extracellular matrix.

INFLAMMATION

Exposure of the skin to UV radiation or environmental pollutants initially causes localized inflammatory response involving innate immunity, and later adaptive immunity involving the T- and B-lymphocytes[44-48]. The initial inflammation results in the release of cytokines, such as interleukins (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)[45]. These cytokines activate I-κB kinase, which activates the NF-κB transcriptional factor, amplifying the expression of inflammatory mediators[44]. The activation of adaptive immunity causes the release of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, which drives the activation of Janus tyrosine kinases, induces dimerization of signal transducers of transcription, and increased expression of additional inflammatory mediators, such as Immunoglobulin E (IgE)[44-48]. IgE antibodies cause the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators from basophils and mast cells[48].

Cellular inflammation is also associated with increased production of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and IL-8[20,21]. VEGF binds to receptor tyrosine kinase to activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and thereby the activation of several transcription factors such as c-fos[34]. TGF-β binds to its receptors to activate SMADs that regulate the expression of cell cycle and the ECM[34]. Finally, IL-8 binds to its chemokine receptors and mediates its effects through several means, including the increase in intracellular calcium levels[44,45].

Both innate and adaptive immunity are regulated by VD[49]. VD deficiency, as well as that of its receptor, is associated with inflammation, increased serum levels of inflammatory factors, and inflammatory diseases[50,51]. VD supplementation inhibits the activity of NF-κB in peritoneal macrophages[52]. VD inhibits angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro by decreasing IL-8 expression in human fibroblasts[53,54]. It also decreases the levels of IL-1 and IL-8 in UVA-irradiated fibroblasts, but not in UVB-irradiated or non-irradiated fibroblasts, suggesting that VD specifically curbs inflammatory reactions to UVA exposure[34]. Additionally, VD inhibits the expression of the inflammatory mediators IL-1 and TNF-α, and the angiogenesis factors TGF-β and VEGF at protein and mRNA levels in melanoma cells, implicating transcriptional regulation[35]. The stated conclusions on the effects of VD on the inflammatory factors have been determined through in vitro experiments, in which non-irradiated, UVA-radiated, or UVB-radiated human dermal fibroblasts, and melanoma cells were incubated with different concentrations of VD[34,35]. The culture media were examined by ELISA for protein levels of the inflammatory and angiogenic factors IL-1, IL-8, TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF. mRNA levels of these inflammatory and angiogenic factors were measured by reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

Cell viability

Cellular oxidative damage causes cell death through the intrinsic apoptosis pathway[55], whereas inflammatory players cause cell death via extrinsic apoptosis[56]. Conversely, oxidative effects and inflammatory mediators facilitate resistance to cell death through mutations in protooncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, or through the activation of the protein kinase B (PKB) pathway.

DNA damage activates ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein), leading to p53 activation[44,57,58]. Then p53 activates the pro-apoptotic factor Bax, allowing the release of cytochrome C into the cytoplasm and the subsequent activation of caspases[35,44]. Also, the increase in p53 activity activates p21 triggering its binding to cyclin-dependent kinases to cause cell cycle arrest[44]. Conversely, mutations in p53, due to oxidative damage, facilitate carcinogenesis[59].

Inflammatory cytokines are implicated in the extrinsic apoptotic pathway by activating Fas-associated death domain and TNF receptor-associated death domain. These cause the release of Bax from Bcl-2 (antiapoptotic protein) in the mitochondrial membrane and, therefore, the activation of the caspases[44,60]. Conversely, activation of the PKB pathway retains the binding of Bcl-2 to Bax in the resistance to apoptosis[44,60].

VD increases the viability of UVB radiated fibroblasts and the p53 promoter activity in melanoma cells, suggesting cell-specific protective effects [Figure 2][34,35]. VDR knock-out mice display reduced expression of p53 and premature aging[61]. The supplementation of VD results in an increase of p53 expression and photoprotection[62]. p53 promoter activity has been assessed by co-transfecting cells with p53 promoter cDNA linked to firefly luciferase and thymidine kinase (TK) promoter linked to renilla luciferase (to normalize transfection efficiency) and measuring luciferase activity following supplementation with VD[35].

EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX REMODELING

Oxidative damage and inflammation are associated with increased ECM remodeling, promoting skin wrinkling and cancer progression[63]. There is a coordinated regulation between inflammatory mediators and the ECM proteins[63,64]. The primary structural ECM proteins are collagen and elastin, and the primary ECM remodeling or degrading enzymes are matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and elastase. A loss of collagen and an increase in MMPs/elastases is associated with skin aging and cancer. Intrinsic aging is associated with loss of elastin, whereas photoaging is associated with solar elastosis[65,66]. The action of MMPs is based on substrate specificity or the elements in its promoters. Therefore, different MMPs can be found. Based on substrate specificity, MPPs can be classified as: interstitial collagenases that cleave the fibrillar collagens (predominantly MMP-1), the gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), and stromelysins (MMP-3 and MMP-10) that cleave primarily the basement membrane, the membrane-type MMPs that cleave pro-MMPs, and the other MMPs such as metalloelastase (MMP-12) that cleaves the basement membrane and elastin[65]. MMPs are alternatively also classified according to their regulatory promoter elements: group I that contain TATA box and activator protein-1 (AP-1 site); group II, which bears no AP-1 site; and group III, which display no TATA box or AP-1 sites[66]. The transcription factor AP-1 is stimulated by the MAPK pathway, which is activated by cellular inflammation and angiogenesis[44]. MMP activity is inhibited by the tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP). The four TIMPs (TIMP-1, -2, -3, -4) bind to all of the MMPs, though TIMP-1 has a preference for MMP-1 and TIMP-2 to MMP-2[67]. The TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 are inducible, TIMP-2 is constitutive, and TIMP-4 exhibits tissue specificity[67]. ECM remodeling is associated with increased expression of MMPs and elastase, and reduced expression of TIMPs and collagen[67].

VD improves ECM proteins regulation in fibroblasts and melanoma cells[34,35] [Figure 2]. VD promotes the expression of collagen, whereas it inhibits the expression of elastin[68,69]. VD stimulates the expression of collagen by transcriptional mechanism, in non-irradiated and UVA-irradiated fibroblasts, though not in UVB-irradiated fibroblasts[35]. In UVA-irradiated fibroblasts, VD also stimulates heat shock protein-47 (HSP-47), a chaperone involved in the formation of collagen fibers, but again not in non-irradiated and UVB-irradiated fibroblasts[35]. VD also inhibits elastin promoter activity in non-irradiated and UV-irradiated fibroblasts[35]. It has also been described that VD inhibits elastase activity directly and its expression in non-irradiated, and UVA-irradiated fibroblasts, though not in UVB-irradiated fibroblasts[35]. Elastase activity can be measured by incubating the enzyme with VD followed by the addition of its substrate, whose degradation to a colored product can be followed by spectrophotometrically (Elastin Products Co)[35]. VD also inhibits MMP-1 and MMP-2 protein levels in melanoma cells[33].

The stated conclusions on the effects of VD on the extracellular matrix remodeling were determined through in vitro experiments, in which non-irradiated, UVA-irradiated, or UVB-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts, and melanoma cells were incubated for 24 h with different concentrations of VD, and expression of different proteins was measured by RT-qPCR and/or ELISA. Protein levels of type I collagen, elastin, MMP-1, and MMP-2 were measured in the media, and protein levels of HSP-47 were measured in cells using ELISA. The RT-qPCR was used to measure mRNA levels of MMP-1 and MMP-2. Fibroblasts were co-transfected with COL1α1 promoter-firefly luciferase or elastin promoter-firefly luciferase and TK promoter-Renilla luciferase plasmids for 24 h, prior to the dosing with UV radiation and/or VD; and firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured sequentially to determine the normalized type I collagen or elastin promoter activities. Melanoma cells were co-transfected with the MMP-1 promoter-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) plasmid and RSV2-β Galactosidase (β-GAL) prior to incubation with or without VD, and the cells were examined for CAT expression and β-GAL activity to determine the normalized MMP-1 promoter activity. Collectively, VD strengthens the ECM and is beneficial to the prevention of photoaging and carcinogenesis.

CONCLUSION

VD facilitates skin health through its action on dermal fibroblasts and/or melanoma cells by preventing oxidative DNA damage, membrane damage, and lipid peroxidation, and by stimulating superoxide dismutase expression ameliorating the effects of oxidative stress[34,35]. In addition, VD reduced the expression of IL-1, TNF-α, IL-8, TGF-β, and VEGF, decreasing inflammation[35,53,54] and also preventing cell death in UVB-irradiated fibroblasts, increasing p53 promoter activity[34,35]. At the extracellular level, VD stimulated the expression of type I collagen and inhibited elastase, elastin, and MMPs, particularly MPP-1 and MPP-2, with beneficial ECM effects[68,69].

In summary, the data reviewed here suggested that VD supported the maintenance of skin health with anti-aging[70] and anti-carcinogenic effects. The currently recommended doses of VD (as cholecalciferol, D3) are 400 units (1 unit = 0.025 μg VD) for children until one year of age, 600 units for people ranging from 1 year through 70 years of age, and 800 for people over 70 years of age[28,71,72]. The physiological dose of VD is 2.5-10 μg (1 μg = 40 units), and the pharmacological dose of VD (as cholecalciferol, D3, or ergocalciferol, D2) is 0.625-5 mg for 1-3 months to treat VD deficiency[73]. The other commonly used VD metabolites or analogs, paricalcitol, doxercalciferol, and calcitriol, are used to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism[47]. The current research on VD effects strongly advocates for dietary supplementation with VD. Further, the anti-photoaging and anti-carcinogenic effects of VD could be potentiated by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2 pathway, which is inhibited by NSAIDs, has been implicated in the etiology of cancer, along with the inflammatory cytokines. Piroxicam and Diclofenac (NSAIDs) inhibit MMP-2 activity in a fibrosarcoma cell line. Both NSAIDS are suitable for field cancerization treatment of actinic keratosis. It is inferred that the combination of Diclofenac, or other NSAIDS, with VD, would provide added benefit.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization: Philips N

Writing - original draft preparation: Philips N, Portillo-Esnaola M

Writing - review and editing: Philips N, Portillo-Esnaola M

Figures: Portillo-Esnaola M, Samuel P, Gallego-Rentero M

Initial bibliographic research: Keller T, Franco J

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipNone.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2005;16:83-95.

2. Eassa HA, Eltokhy MA, Fayyaz HA, et al. Current topical strategies for skin-aging and inflammaging treatment: science versus fiction. J Cosmet Sci 2020;71:321-50.

3. Moreno R, Nájera L, Mascaraque M, Juarranz Á, González S, Gilaberte Y. Influence of serum vitamin D level in the response of actinic keratosis to photodynamic therapy with methylaminolevulinate. J Clin Med 2020;9:398.

4. Haussler MR, Jurutka PW, Mizwicki M, Norman AW. Vitamin D receptor (VDR)-mediated actions of 1α,25(OH)2 vitamin D3: genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;25:543-59.

5. Vuolo L, Di Somma C, Faggiano A, Colao A. Vitamin D and cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:58.

6. Bikle DD. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem Biol 2014;21:319-29.

7. Tongkao-On W, Carter S, Reeve VE, et al. CYP11A1 in skin: an alternative route to photoprotection by vitamin D compounds. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2015;148:72-8.

8. Slominski AT, Kim TK, Li W, Yi AK, Postlethwaite A, Tuckey RC. The role of CYP11A1 in the production of vitamin D metabolites and their role in the regulation of epidermal functions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014;144 Pt A:28-39.

9. Jeon SM, Shin EA. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Exp Mol Med 2018;50:1-14.

10. Slominski AT, Chaiprasongsuk A, Janjetovic Z, et al. Photoprotective properties of vitamin D and lumisterol hydroxyderivatives. Cell Biochem Biophys 2020;78:165-80.

11. Markiewicz A, Brożyna AA, Podgórska E, et al. Vitamin D receptors (VDR), hydroxylases CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 and retinoid-related orphan receptors (ROR) level in human uveal tract and ocular melanoma with different melanization levels. Sci Rep 2019;9:9142.

12. Aschrafi A, Meindl N, Firla B, Brandes RP, Steinhilber D. Intracellular localization of RORalpha is isoform and cell line-dependent. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1763:805-14.

13. Slominski AT, Brożyna AA, Zmijewski MA, et al. Vitamin D signaling and melanoma: role of vitamin D and its receptors in melanoma progression and management. Lab Invest 2017;97:706-24.

14. Gu Y, Han J, Jiang C, Zhang Y. Biomarkers, oxidative stress and autophagy in skin aging. Ageing Res Rev 2020;59:101036.

16. Cole MA, Quan T, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Extracellular matrix regulation of fibroblast function: redefining our perspective on skin aging. J Cell Commun Signal 2018;12:35-43.

17. Bocheva G, Slominski RM, Slominski AT. The impact of vitamin D on skin aging. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:9097.

19. Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, et al. Oxidative stress:harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:8416763.

20. Philips N, Samuel M, Parakandi H, et al. . Vitamins in the therapy of inflammatory and oxidative diseases. In: Atta-ur-Rahman, editor. Frontiers in clinical drug research-anti allergy agents. Bentham science; 2013; p. 240-64.

21. Philips N, Siomyk H, Bynum D, Gonzalez S. Skin cancer, polyphenols, and oxidative stress. Cancer 2014; doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-405205-5.00026-x.

22. Philips N, Devaney J. Beneficial regulation of type I collagen and matrixmetalloproteinase-1 expression by estrogen, progesterone, and its combination in skin fibroblasts. J Am Aging Assoc 2003;26:59-62.

24. Terra VA, Souza-Neto FP, Pereira RC, et al. Time-dependent reactive species formation and oxidative stress damage in the skin after UVB irradiation. J Photochem Photobiol B 2012;109:34-41.

25. Philips N, Hwang H, Chauhan S, Leonardi D, Gonzalez S. Stimulation of cell proliferation and expression of matrixmetalloproteinase-1 and interluekin-8 genes in dermal fibroblasts by copper. Connect Tissue Res 2010;51:224-9.

26. Philips N, Burchill D, O'Donoghue D, Keller T, Gonzalez S. Identification of benzene metabolites in dermal fibroblasts as nonphenolic: regulation of cell viability, apoptosis, lipid peroxidation and expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 and elastin by benzene metabolites. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2004;17:147-52.

27. Matsumura Y, Ananthaswamy HN. Toxic effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2004;195:298-308.

28. D'Orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, Scott T. UV radiation and the skin. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:12222-48.

29. Nishimura S. Involvement of mammalian OGG1(MMH) in excision of the 8-hydroxyguanine residue in DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 2002;32:813-21.

30. Agar NS, Halliday GM, Barnetson RS, Ananthaswamy HN, Wheeler M, Jones AM. The basal layer in human squamous tumors harbors more UVA than UVB fingerprint mutations: a role for UVA in human skin carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:4954-9.

31. Portillo-Esnaola M, Rodríguez-Luna A, Nicolás-Morala J, et al. Formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers after UVA exposure (Dark-CPDs) is inhibited by an hydrophilic extract of polypodium leucotomos. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:1961.

32. Chaudhuri RK, Meyer T, Premi S, Brash D. Acetyl zingerone: an efficacious multifunctional ingredient for continued protection against ongoing DNA damage in melanocytes after sun exposure ends. Int J Cosmet Sci 2020;42:36-45.

33. Eiberger W, Volkmer B, Amouroux R, Dhérin C, Radicella JP, Epe B. Oxidative stress impairs the repair of oxidative DNA base modifications in human skin fibroblasts and melanoma cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:912-21.

34. Philips N, Ding X, Kandalai P, Marte I, Krawczyk H, Richardson R. The beneficial regulation of extracellular matrix and heat shock proteins, and the inhibition of cellular oxidative stress effects and inflammatory cytokines by 1α, 25 dihydroxyvitaminD3 in non-irradiated and ultraviolet radiated dermal fibroblasts. Cosmetics 2019;6:46.

35. Philips N, Samuel P, Keller T, Alharbi A, Alshalan S, Shamlan SA. Beneficial regulation of cellular oxidative stress effects, and expression of inflammatory, angiogenic, and the extracellular matrix remodeling proteins by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in a melanoma cell line. Molecules 2020;25:1164.

36. Philips N, Keller T, Hendrix C, et al. Regulation of the extracellular matrix remodeling by lutein in dermal fibroblasts, melanoma cells, and ultraviolet radiation exposed fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res 2007;299:373-9.

37. Philips N, Conte J, Chen YJ, et al. Beneficial regulation of matrixmetalloproteinases and their inhibitors, fibrillar collagens and transforming growth factor-beta by Polypodium leucotomos, directly or in dermal fibroblasts, ultraviolet radiated fibroblasts, and melanoma cells. Arch Dermatol Res 2009;301:487-95.

38. Philips N, Samuel P, Lozano T, et al. Effects of humulus lupulus extract or its components on viability, lipid peroxidation, and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in melanoma cells and fibroblasts. Madridge J Clin Res 2017;1:15-9.

39. Portillo M, Mataix M, Alonso-Juarranz M, et al. The aqueous extract of Polypodium leucotomos (Fernblock®) regulates opsin 3 and prevents photooxidation of melanin precursors on skin cells exposed to blue light emitted from digital devices. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10:400.

40. Song EJ, Gordon-Thomson C, Cole L, et al. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces several types of UV-induced DNA damage and contributes to photoprotection. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013;136:131-8.

41. Gordon-Thomson C, Gupta R, Tongkao-on W, Ryan A, Halliday GM, Mason RS. 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances cellular defences against UV-induced oxidative and other forms of DNA damage in skin. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2012;11:1837-47.

42. Ke CY, Yang FL, Wu WT, et al. Vitamin D3 reduces tissue damage and oxidative stress caused by exhaustive exercise. Int J Med Sci 2016;13:147-53.

43. Wimalawansa SJ. Vitamin D deficiency: effects on oxidative stress, epigenetics, gene regulation, and aging. Biology (Basel) 2019;8:30.

44. Lodish H, Berk A, Kaiser CA, et al. . Molecular cell biology. 8th ed. W.H. Freeman and Company; 2008. p. 1056-112.

45. Kindt TJ, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA. . Kuby Immunology. 6th ed. W.H. Freeman and Company; 2007. p. 312-8.

46. Philips N, Samuel P, Samuel M, Perez G, Khundoker R, Alahmade G. Interleukin-4 signaling pathway and effects in allergic diseases. CST 2018;13:76-80.

47. Philips N. Inhibition of interleukin-4 signalling in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and allergic asthma. Glob J Allergy 2015; doi: 10.17352/2455-8141.000019.

48. Geha RS, Jabara HH, Brodeur SR. The regulation of immunoglobulin E class-switch recombination. Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:721-32.

49. Wei R, Christakos S. Mechanisms underlying the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by vitamin D. Nutrients 2015;7:8251-60.

51. Chen Y, Xu T. Association of vitamin D receptor expression with inflammatory changes and prognosis of asthma. Exp Ther Med 2018;16:5096-102.

52. Cohen-Lahav M, Shany S, Tobvin D, Chaimovitz C, Douvdevani A. Vitamin D decreases NFkappaB activity by increasing IkappaBalpha levels. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:889-97.

53. Mantell DJ, Owens PE, Bundred NJ, Mawer EB, Canfield AE. 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res 2000;87:214-20.

54. Nakashyan V, Tipton DA, Karydis A, Livada R, Stein SH. Effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and 20(OH)D3 on interleukin-1β-stimulated interleukin-6 and -8 production by human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontal Res 2017;52:832-41.

55. Wu CC, Bratton SB. Regulation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway by reactive oxygen species. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;19:546-58.

56. Goldar S, Khaniani MS, Derakhshan SM, Baradaran B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:2129-44.

57. Bitomsky N, Hofmann TG. Apoptosis and autophagy: regulation of apoptosis by DNA damage signalling - roles of p53, p73 and HIPK2. FEBS J 2009;276:6074-83.

58. Hafner A, Bulyk ML, Jambhekar A, Lahav G. The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20:199-210.

59. Bosch R, Philips N, Suárez-Pérez JA, et al. Mechanisms of photoaging and cutaneous photocarcinogenesis, and photoprotective strategies with phytochemicals. Antioxidants (Basel) 2015;4:248-68.

61. Keisala T, Minasyan A, Lou YR, et al. Premature aging in vitamin D receptor mutant mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2009;115:91-7.

62. Gupta R, Dixon KM, Deo SS, et al. Photoprotection by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 is associated with an increase in p53 and a decrease in nitric oxide products. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:707-15.

63. Philips N, Keller T, Holmes C. Reciprocal effects of ascorbate on cancer cell growth and the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and transforming growth factor-beta. Cancer Lett 2007;256:49-55.

64. Philips N, Dulaj L, Upadhya T. Cancer cell growth and extracellular matrix remodeling mechanism of ascorbate; beneficial modulation by P. leucotomos. AntiCancer Res 2009;29:3233-8.

66. Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J Cell Physiol 2007;211:19-26.

67. Verstappen J, Von den Hoff JW. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): their biological functions and involvement in oral disease. J Dent Res 2006;85:1074-84.

68. Dobak J, Grzybowski J, Liu F, Landon B, Dobke M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 increases collagen production in dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci 1994;8:18-24.

69. Hinek A, Botney MD, Mecham RP, Parks WC. Inhibition of tropoelastin expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Connect Tissue Res 1991;26:155-66.

70. Bocheva G, Slominski RM, Slominski AT. Neuroendocrine aspects of skin aging. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:2798.

72. Vitamin D. Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/#h2 [Last accessed on 12 Jan 2022].

73. Gardner DG, Shoback D. . Greenspan’s basic and clinical endocrinology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill Medical; 2011.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Philips N, Portillo-Esnaola M, Samuel P, Gallego-Rentero M, Keller T, Franco J. Anti-aging and anti-carcinogenic effects of 1α, 25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 on skin. Plast Aesthet Res 2022;9:4. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-9264.2021.83

AMA Style

Philips N, Portillo-Esnaola M, Samuel P, Gallego-Rentero M, Keller T, Franco J. Anti-aging and anti-carcinogenic effects of 1α, 25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 on skin. Plastic and Aesthetic Research. 2022; 9: 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-9264.2021.83

Chicago/Turabian Style

Philips, Neena, Mikel Portillo-Esnaola, Philips Samuel, Maria Gallego-Rentero, Tom Keller, Jan Franco. 2022. "Anti-aging and anti-carcinogenic effects of 1α, 25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 on skin" Plastic and Aesthetic Research. 9: 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-9264.2021.83

ACS Style

Philips, N.; Portillo-Esnaola M.; Samuel P.; Gallego-Rentero M.; Keller T.; Franco J. Anti-aging and anti-carcinogenic effects of 1α, 25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 on skin. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 2022, 9, 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-9264.2021.83

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 9 clicks

Cite This Article 9 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.